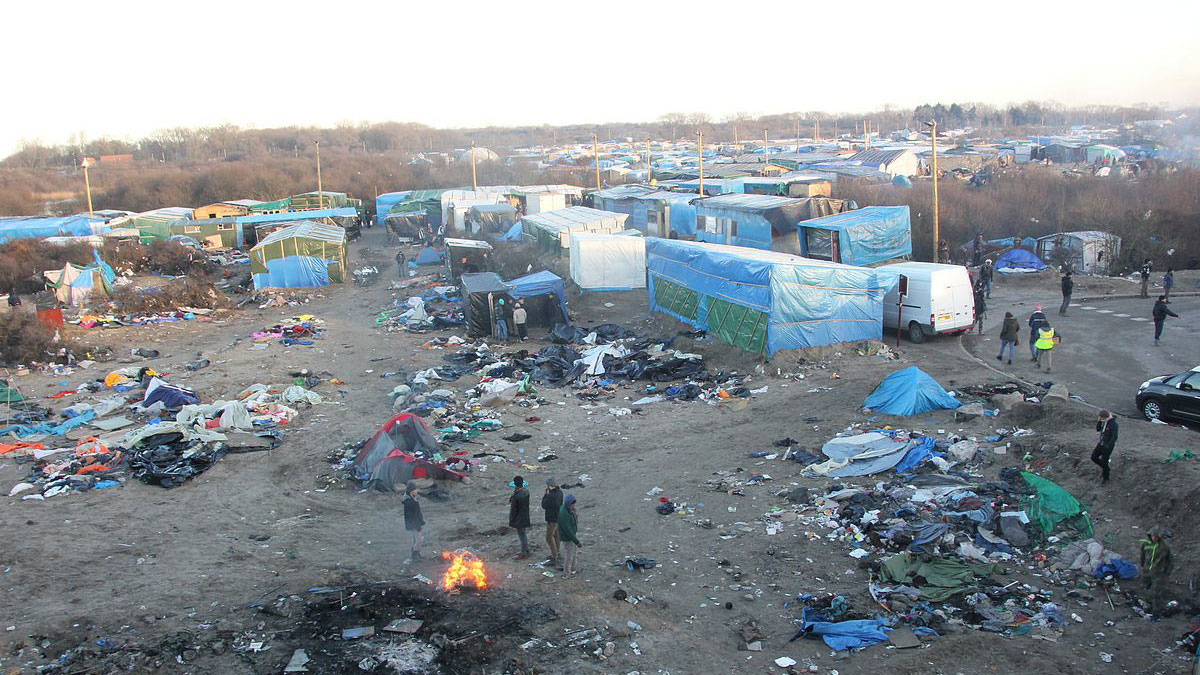

Sarah is 25 years old and spent a year and a half working with the refugees from Calais, she arrived in Calais over 10,000 refugees gathered in.

It is now estimated that around 700 refugees remain in the Calais area. Since the beginning, non-governmental organizations try to ensure the essentials of food, clothing, hygiene, and generators. Some also try to provide legal advice and information to the refugees of Calais.

I was sitting drinking tea with one of the refugees when I noticed that he had only sandals and a sock. We were in the middle of winter. I took off one of my socks and gave it to him. After a few months, he found me via Facebook and sent me a picture of the sock I gave him, one of the few things he had left from the time in Calais.”

Sarah smiles sadly as she remembers her time in Calais:

every day there was worse news than the day before. When we think it cannot become worse we deceive ourselves. The only thing we can do is to keep working.”

Sarah’s organization is facing financial difficulties, all volunteers and young people, Sarah, and her colleagues row against the tide, but with determination.

In winter the situation is complicated by the cold and the rain that beats the tents that are never enough for everyone. Men, women, and children in a state of emergency that has been going on since 1999 and peaked in 2016. After the dismantling of 2016, the camp that had grown in a small woodland near the entrance of the Channel Tunnel and the port area of Calais is not called camp or jungle anymore. Today the tents and other improvised shelters are scattered.

Who are the refugees from Calais?

The refugees from Calais fled war, hunger, and persecution in their home countries, hoping for a better and safer life in Europe. But what they found on a day-to-day basis was police brutality, precarious life situations, and uncertainty about whether they ever had the right to asylum or see their families again. The majority came from Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Sudan.

As Sarah tells us:

most of them wanted to get to the UK because they have family or friends there, because they already speak English, or because they can find a job there. They do not want to live on subsidies, they want to rebuild their lives.”

This testimony was proven by the first survey of refugees by Refugee Rights Europe in October 2017 – 92% answered the did not want to stay in France, but cross the Channel and go to the UK.

In 2017, and after complaints from humanitarian organizations, the French government provided only a few toilets and water point access which is not providing any dignity to these refugees who are still living in inhuman conditions.

Refugees in Calais found no shelter and continued to sleep outdoors, including families with young children.

“They all suffer from psychological disorders, the traumas, the brutality they have been and are exposed to are extremely violent,” says Sarah.

Macron and his new policy

The main objective of the French government is to eliminate the so-called attraction factors and force the migrants to leave the country as soon as possible.

Despite protests from NGOs, lawyers and the judges’ strike of the French National Asylum Court in early 2018, the new government law on migration was approved and extended the period of detention for foreigners awaiting deportation from 45 to 90 days. In addition, the time available to claim asylum since arrival in France has been reduced to 90 days, and up to one year of detention has been established for those who illegally cross the Alps. The new law also gives more power to the police, allowing them to keep undocumented migrants in custody for up to 24 hours, instead of the previous sixteen.

Under no circumstances will we allow the jungle to return”

President Macron in an attempt to distance himself from human misconduct (including accusations from Human Rights Watch), visited Calais in 2018 and told a silent crowd of police: “You must be exemplary, and respect the dignity of every individual. If there are failures, they will be sanctioned in proportion to the confidence we have in you. “According to French newspapers, the public did not applaud.

Macron criticized the volunteers for helping the migrants, who in his opinion encouraged “these men and women to establish themselves illegally,” to which he added: “Under no circumstances will we allow the jungle to return.”

Sarah says most of the refugees try to organize themselves and find a “lift” on a truck to cross the border.

The court

In Paris, about 300km away Maître Ouled runs for another hearing, it is in her office that Sarah is in training. Both just ended a meeting with one more Afghan client.

… “and then you were tortured, can you tell me exactly how? …” Maître Ouled repeats a question that has become almost a routine, “yes, they took me …” the young man reports the events, the torture and shows the scars and marks that he has on his body. Maître Ouled hears stories like this day after day:

“It is very difficult to be a refugee lawyer, the emotional price is enormous and many of my colleagues are giving up, the new law is inhumane.”

Many Afghans who arrive in France have seen their asylum application refused in Germany. According to the German courts, there is no immediate danger or life peril in Afghanistan nor are there human rights problems and therefore they can return “safely.” Interestingly, however, the German Foreign Ministry seems to take a different view when it comes to the safety and physical integrity of German citizens and warns them to avoid traveling to Afghanistan. Pushed from country to country, France may not be the last destination and many of the refugees will be deported.

The streets of Paris, the city where I interviewed Sarah are full of people living in the street underneath bridges and huddling in the metro stations during the day. The law office is flooded with phone calls of new clients, asylum seekers who’s stories are heartbreaking.

Some of the lawyer with whom I spoke in the last months have depression, leave their profession, suffer from continues tiredness, feel exhausted and one even had a heart attack.

When you have a conscience, a heart, this job eats you up. You have to stay focused one case a time, and even so, it is very hard. The moment you stop feeling, that’s the moment you should stop working on these cases”.

Governments need to address the source of the conflicts that are the root causes of the so-called refugee crisis, otherwise, the horror will never end.