Em Roma, depois do fracasso do acordo de 2019 com Pequim, as velhas alianças ocidentais estão de volta. Uma análise de Ludovica Meacci, na Foreign Policy, de leitura obrigatória. Sobretudo, para Marcelo e António Costa…

Italy Has Learned a Tough Lesson on China

Old Western alliances are back on the table after a 2019 deal failed.

By Ludovica Meacci, a freelance China researcher, focused on European Union-China relations.

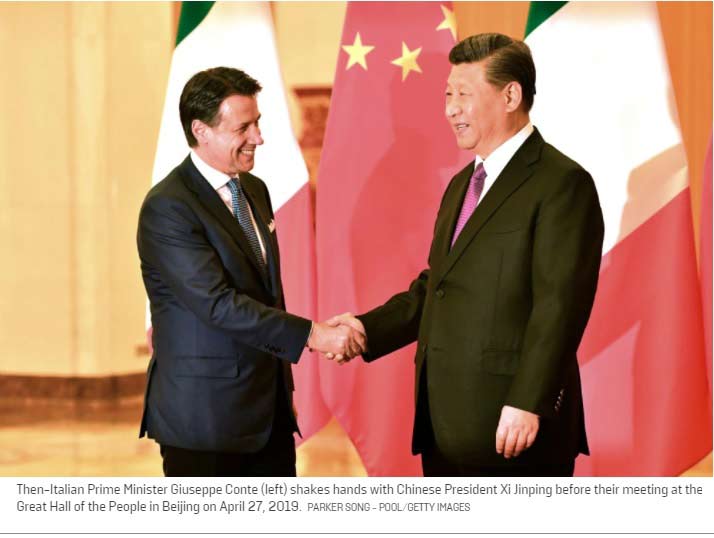

“When Italy signed a memorandum of understanding supporting China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2019, then-Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte had been governing for less than a year. The governing coalition of the populist Five Star Movement and the right-wing League party could not seem to agree on what the memorandum was meant to codify. Previously, Beijing had not occupied a prominent position in the country’s foreign policy, and discussions around China were limited.

As the protagonists in a dysfunctional coalition jostled, the debate over the memorandum and Italian interests toward China occurred only through their electoral programs. For the Five Star Movement, China represented an opportunity to export products made in Italy, while the League party insisted on the need to safeguard national interests.

Before signing the agreement, warnings came on many fronts. Both American and European leaders cautioned Rome against signing a bilateral deal with Beijing. Conte, on the other hand, was quick to reassure the public that the agreement was purely a commercial one and that it favored Italian national interests.

Two governments and one prime minister later, Italy has learned its lesson.

(…)

Italy’s reemphasis on its traditional alliances comes with the realization that the extravagant commercial promises made around 2019 have not been met. As highlighted in a report by the Torino World Affairs Institute published in late 2020, “the calculations were optimistic at best, if not entirely fallacious.” Ironically, in 2020, other European countries that have not signed up for the Belt and Road Initiative such as France and Germany did equal or better trade with Beijing than Rome did. Prospective collaborations between China and Italy in a number of sectors enshrined in the memorandum did not materialize.

The botched handling of the Belt and Road memorandum has come with severe political costs. As a member of the G-7, a founding member of both the EU and NATO, and the third-largest economy of the eurozone, Italy endorsing the Belt and Road Initiative gave Chinese President Xi Jinping’s pet project a significant boost at home and abroad. On the other hand, joining the Belt and Road meant that Rome became viewed as “the European weak link in the power struggle with China,” Politico reported, and not only for the United States. While Italy was signing the memorandum, France’s President Emmanuel Macron highlighted the need for a “geopolitical and strategic relationship” with China. Insisting on ending the “European naivety” toward Beijing, Macron warned against “discuss bilaterally agreements on the new Silk Road.” Similar concerns have also been raised by Berlin through less public channels.

In addition to reputational damage, the participation in the Belt and Road Initiative cost Italy a seat at the negotiating table. When the EU and China rushed to finish off the last details of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment in December 2020, Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel joined European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen together with European Council President Charles Michel in a videoconference with Xi. Although it was argued that Merkel’s and Macron’s attendance was justified by their roles in the rotating EU presidency, the presence of the French president irked Italy’s Conte, himself absent from the talk. Then-Undersecretary of State for Foreign Affairs Ivan Scalfarotto from the Italia Viva party linked such unusual arrangements with Italy’s signature of the memorandum of understanding. In his view, signing the memorandum cost Rome its reputation as a trustworthy negotiating partner.

Rome’s new China policy under the Draghi administration thus seeks a return to its “historical anchors” and is showing a clearer vision on Italy’s international posture. A stronger alignment with the European and trans-Atlantic stance is exemplified by the endorsement of a green alternative to the Belt and Road, announced at the G-7 meeting this month. While each member has different views on the geographical scope of the project, they “broadly agree on the need for a more transparent alternative to the Chinese program.”

(…)

Italy’s political flirtation with China may have turned out to be only a brief interlude. Draghi’s declaration at the G-7 highlights that Rome intends to pursue a frank China policy, to cooperate where possible while bearing in mind that Beijing does not play by multilateral rules and does not share a democratic vision of global governance.

This new realpolitik aligns Italy with the tripartite definition of the 2019 EU-China Strategic Outlook, which depicts Beijing simultaneously as a negotiation partner, economic competitor, and systemic rival. It comes at a time of fervent debate in Brussels over not only the EU’s relationship with China but also its regional interests in the Indo-Pacific and its ties with like-minded partners, including Taiwan, India, and Japan. Italy should seize the opportunity that Draghi represents to signal it is a reliable partner and willing to engage in shaping a cohesive China policy in international forums.

Italy Has Learned a Tough Lesson on China

Exclusivo Tornado / IntelNomics