A geopolítica já não é o que era. “Eppur si muove”, dizia o outro, muito baixinho e contra todas aquelas grandes autoridades que não queriam que ela se movesse. As placas tectónicas da geopolítica começaram a mover-se, há já alguns anos, e moveram-se já o suficiente para que o quadro global, saído da II Guerra e “rectificado” pelo fim da Guerra Fria, se tenha alterado profundamente. Também o velho acordo, entre americanos e sauditas, “petróleo contra segurança”, parece ter-se esfumado. O mais recente sinal destas mudanças é a decisão da OPEC+, liderada pelos sauditas, de cortar a produção de petróleo para fazer subir o preço do barril. Em plena crise económica e energética, esta decisão é a pior notícia para a maioria dos países. E deixa claro mais um enfraquecimento (processo começado com Obama) da posição de Washington no xadrez do Médio Oriente. Aqui se regista a síntese que a insuspeita Foreign Policy faz desta “evolução”…

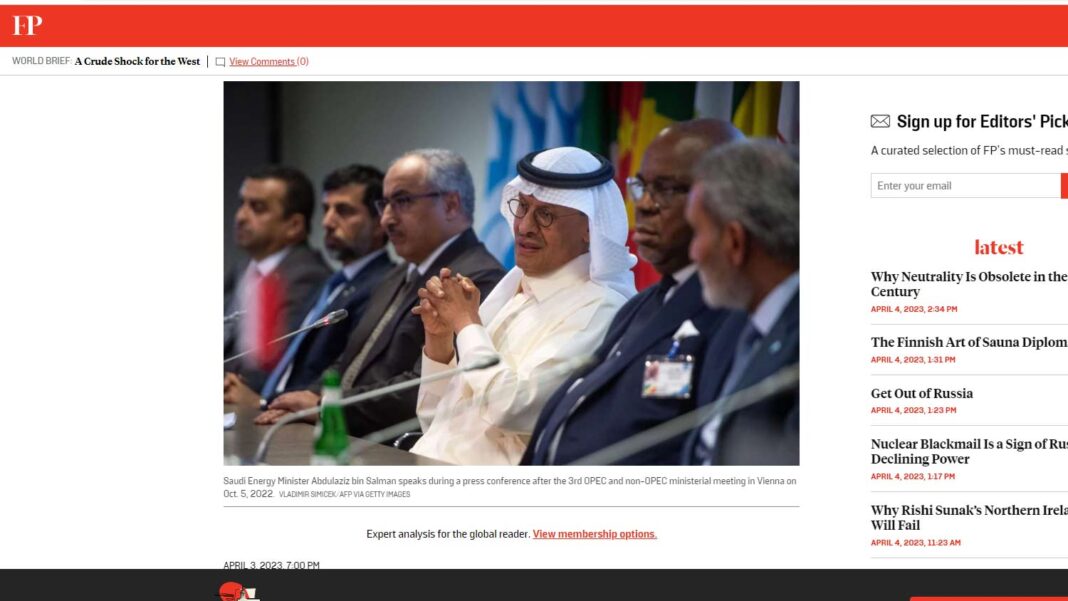

Saudi Arabia’s Oil Win

A crude shock for the West

A trip to the gas pump may soon come with sticker shock after OPEC+ announced another set of cuts to oil production on Sunday. Starting in May, the oil cartel—led by Saudi Arabia and Russia—will slash output by 1.65 million barrels a day in a bid to push up the global price of crude.

The announcement comes amid a crucial shift in the global economy: Beijing’s decision to lift zero-COVID restrictions brought its sizable market back online, increasing demand for crude. This created an opportune moment for OPEC+ nations to raise oil prices, said Raad Alkadiri, managing director of energy, climate, and resources at Eurasia Group.

Crude prices were also beginning to settle after last month’s banking crisis led many hedge funds to fear they were risky assets and sell their oil shares. OPEC+ hopes cutting production will reverse weeks of macroeconomic uncertainty.

But not everyone is happy with the decision—especially in Washington, where the Biden administration is concerned the move will cause gas prices to rise at home and harm efforts to curb high inflation around the world. Central banks are struggling to rein in inflation without raising interest rates—particularly in Europe, which could be facing a looming recession in the coming months.

It’s also yet another sign of the increasingly rocky relationship between the United States and Saudi Arabia. Riyadh has refused to cut ties with Moscow over its invasion of Ukraine, undermining the effectiveness of Western sanctions on Russia. Against U.S. wishes, the cartel announced in October 2022 that it would cut its output by 2 million barrels of oil a day. In response, the United States partially drained its Strategic Petroleum Reserve to support Ukraine and keep oil prices in check.

Last week, however, President Joe Biden said it could take “years” to refill the reserve, meaning the West’s biggest powerhouse has little ammunition left. “They basically used all the bullets they had last year,” said Livia Gallarati, a senior analyst at Energy Aspects. “Now, they’re left with little to nothing that they can do to counterbalance the impact of the OPEC production cuts.”

But it’s the major oil importers in less developed parts of the world that are expected to bear the brunt of rising petrol prices. Alkadiri predicts Pakistan in particular, which is already struggling with a severe energy crisis, could face significant financial pressure.

Since the nations that announced oil cuts are doing so voluntarily, it is possible for OPEC+ to reverse course. But the likelihood of the bloc doing so is minimal, Gallarati said, and the damage to its relationships with Western allies is done.

By Alexandra Sharp, the World Brief writer at Foreign Policy

Exclusivo Tornado / IntelNomics